XNLI, Cross-lingual Natural Language Inference

26 Nov 2020I was recently reading up on the details of XNLI, the cross-lingual natural language inference dataset, trying to understand specifically how it was created, and how it is typically used. I thought it would be useful to document my learning process, at the very least as a service to my future self.

Natural Language Inference (NLI)

First, a brief overview of the task. Natural Language Inference (NLI) is an NLP task that involves two sentences, known as a premise and a hypothesis, and a judgment that indicates if the premise entails the hypothesis. Typically, the judgment takes one of 3 values: entailment, neutral, and contradiction. The table below shows some examples (taken from the MNLI website)

| Premise | Label | Hypothesis |

| Your gift is appreciated by each and every student who will benefit from your generosity. | neutral | Hundreds of students will benefit from your generosity. |

| yes now you know if if everybody like in August when everybody's on vacation or something we can dress a little more casual or | contradiction | August is a black out month for vacations in the company. |

| At the other end of Pennsylvania Avenue, people began to line up for a White House tour. | entailment | People formed a line at the end of Pennsylvania Avenue. |

XNLI: Creation

Typically, this task is done in one language (English), and standard datasets include SNLI, and MNLI. But there’s more to NLP than English, and in a step intended to nudge the field towards multilingual datasets and cross-lingual methods, XNLI was born.

XNLI is inspired by MNLI, but is an entirely new dataset. But unlike most new datasets, it consists only of dev and test sets, with the (English) MNLI training set used for training.

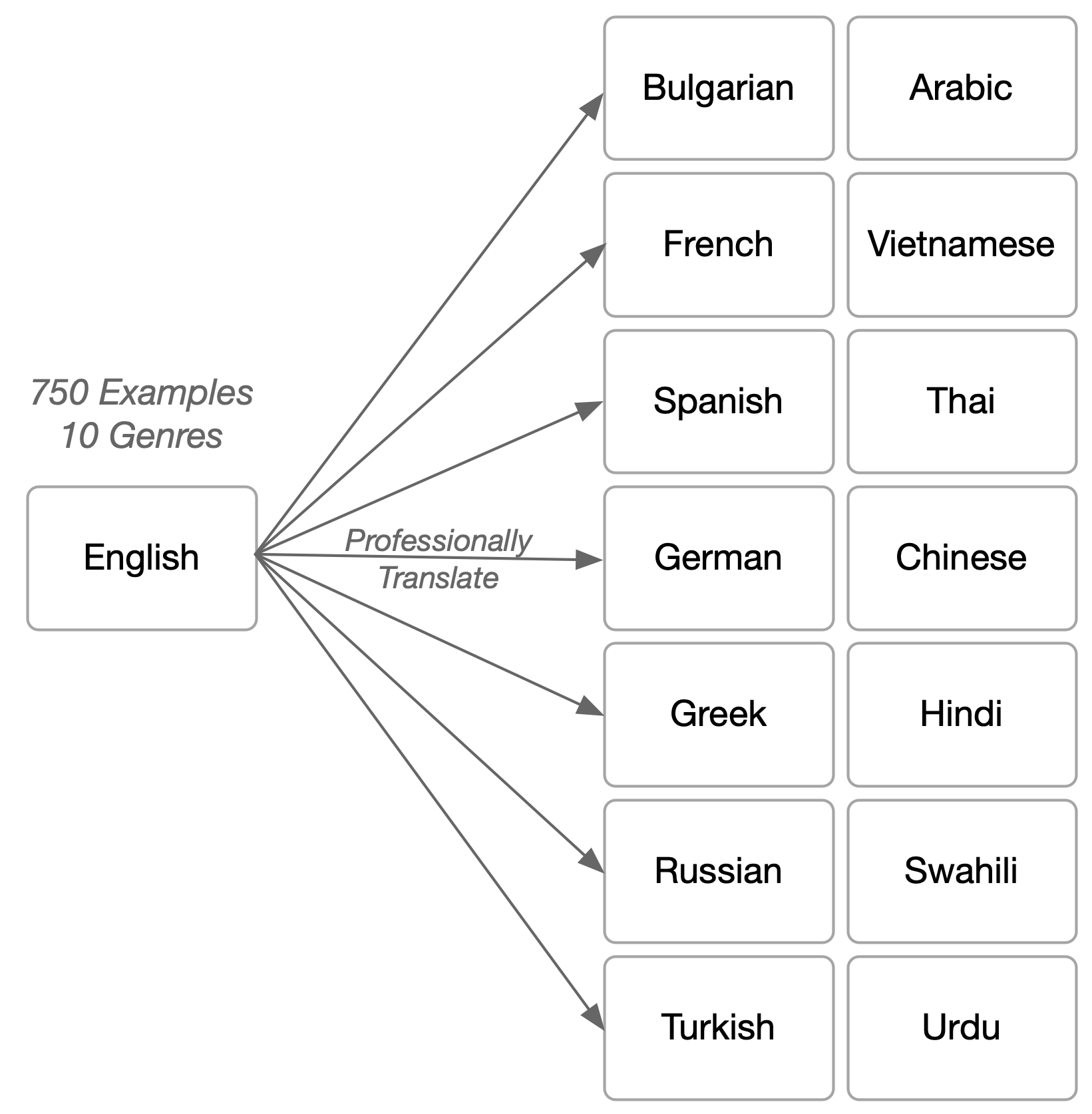

The process of creating the dev and test sets followed closely after MNLI, by selecting and annotating 750 English examples each from 10 different genres, resulting in a dataset with a total of 7500 English examples. These examples were then professionally translated (that is, by humans) into 14 other languages, as shown in the figure below.

So now, for each English example X, there exist parallel examples in French, German, Swahili, etc. This means that the entire dataset consists of \(7500 \cdot 15 = 112,500\) examples.

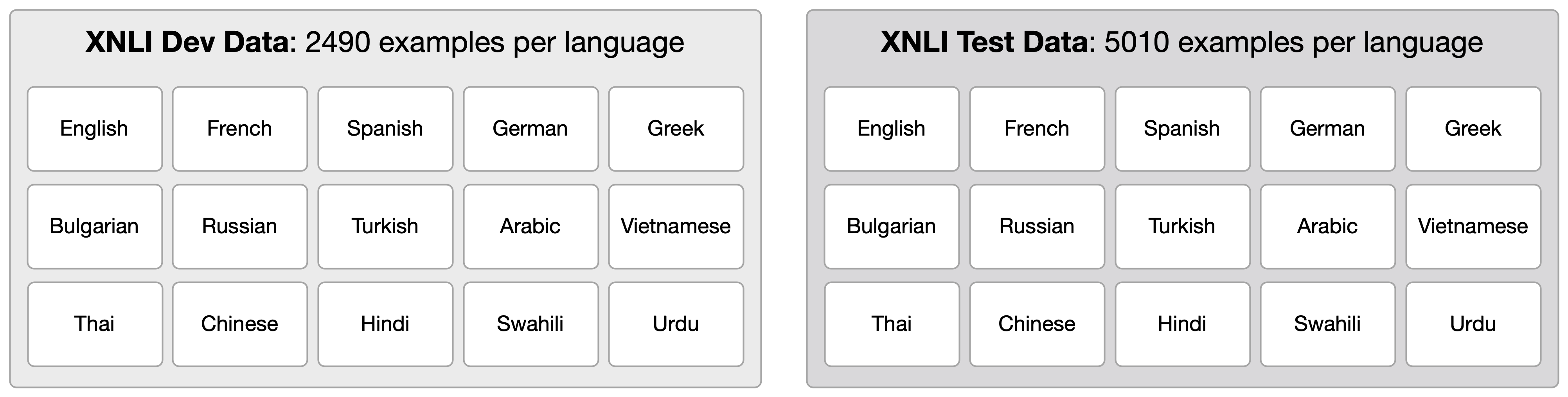

These examples were split into development and test sets, with 2490 and 5010 examples per language respectively.

That’s the big picture for dataset creation. Further details on crowdsourcing, translation, quality control, and statistics can be found in the paper.

XNLI: Usage

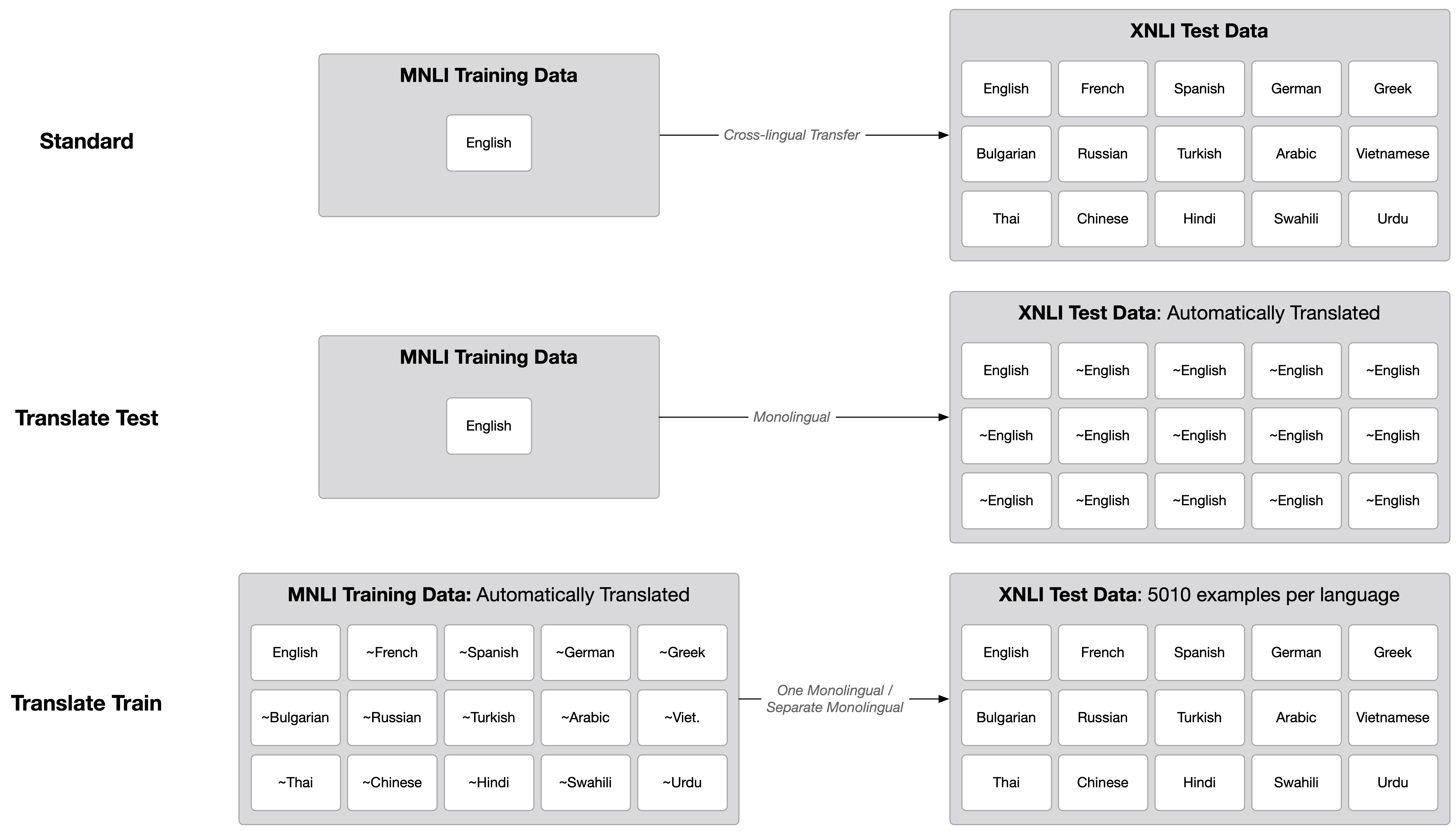

The original paper, and several works since, evaluate on the dataset in at least three distinct ways, as outlined in the figure below.

Note: I use “~English”, as in “approximately English”, to indicate that the text is the output of a machine translation model, subject to error.

In the Standard way, cross-lingual methods train on English MNLI and test on the XNLI dataset, as is. One model must transfer to Bulgarian, and Hindi, and Vietnamese, etc. I call this “Standard” because the purpose of the dataset is to provide a benchmark for cross-lingual language understanding.

Then there are two translation-based baselines. The intuition here is that if machine translation were perfect, then the need for cross-lingual methods would more or less go away. Just translate any data into English, and throw RoElBERPT3a at it. (By the way, one counterargument here is efficiency issues. When doing information retrieval, it would be inconvenient to translate the entire internet into English).

The two baselines are either to translate the many languages in the test data into English (Translate Test), or the English training data into many languages (Translate Train). The quality of translation in each case depends on the source/target language, but also on the state-of-the-art in translation methods, so it should probably be periodically reevaluated.

There are several usage paradigms in the Translate Train case. One may train 15 monolingual models (as reported in XLM-R), or train one big multilingual model (as in mT5. Note: not technically cross-lingual since the target language is present in the training data).

In the original paper, the strongest scores came from the Translate Test baseline, presumably because of the combination of high quality machine translation and English monolingual models.

But as cross-lingual/multilingual methods have improved, the Translate Train method is usually best (see XLM, XLM-R, mT5), presumably because of the powerful multilingual capacity of modern models, combined with 15x more training data.

In my opinion, the Standard evaluation should receive the most attention, and the Translate Train/Test baselines should receive less, even if they tend to get higher scores. Since a supervised MT system is used for the translation baselines, that means parallel data is affecting the final results. But in low-resource cross-lingual scenarios, this parallel text is either not available at scale, or at all. The goal of the dataset is to further cross-lingual efforts, and the Standard evaluation is most faithful to that.

How close are we to human performance today? This isn’t reported in the XNLI paper, but the XTREME benchmark paper argues that human performance on MNLI can be used as a proxy. This value, calculated as part of human evaluations on the GLUE benchmark, is 92.8.

It’s hard to say if this is a reasonable assumption. Is it possible that NLI is harder for humans in Bulgarian, or easier in Turkish? For now, I don’t have anything better, but I wouldn’t be surprised if each language had a different human performance.

The top-performing model as of writing is mT5 (specifically the mT5-XXL model version) at 87.2.